My Groundwork Project centers around the idea of foodlore activism (the telling of food stories with the intent to create positive social change) as a tool for cultural sustainability work. Much of the literature I have explored over the past weeks falls into three general categories: the relationship between folklore and activism, the use of food and foodways to tell stories, and the role of stories in movements for social change.

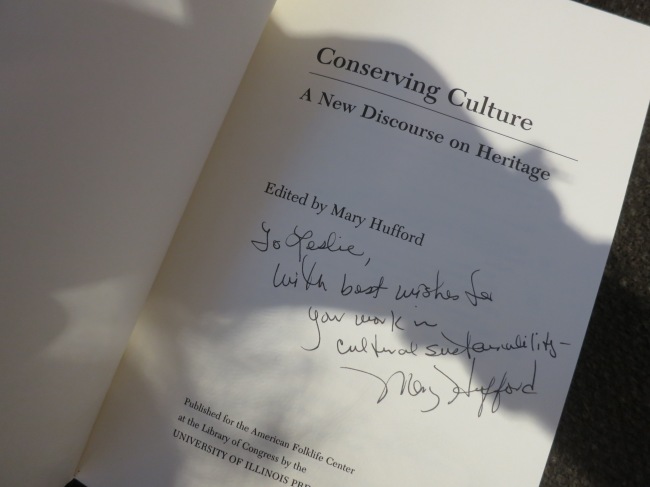

After brief excursions into history and anthropology, folklore has emerged as the most promising field in which to cultivate foodlore activism. Mary Hufford’s “Working in the Cracks: Public Space, Ecological Crisis, and the Folklorist,” Debora Kodish’s “Envisioning Folklore Activism,” and some words of wisdom from City Lore’s Steve Zeitlin all support the shift of the folklorist’s role to that of an activist who calls attention to the everyday performances that give meaning to our lives, particularly when those performances are at risk of being lost or when they bring social issues to light. Additionally, Bill Westerman’s article “Wild Grasses and New Arks: Transformative Potential in Applied and Public Folklore” provides a strong framework upon which to build my argument of foodlore as a transformative art.

Marcie Cohen Ferris offers a number of writings that model how food and foodways tell a collective cultural story; her article “Feeding the Jewish Soul in the Delta Diaspora” is particularly helpful. Jane Zeigelman’s 97 Orchard: An Edible History of Five Immigrant Families in One New York Tenement is another great example of this. Lucy Long’s Culinary Tourism introduces a number of essays that address issues of identity, authenticity, and community, all through the medium of food. There is an ever-increasing variety of quality foodlore-related literature, written from both historical and folkloristic perspectives, focusing on a myriad of cultures and places.

There is also a significant amount of writing on the use of stories in movements for social change. The essays in Stories of Change: Narrative and Social Movements (edited by Joseph E. Davis) and in Telling Stories to Change the World: Global Voices on the Power of Narrative to Build Community and Make Social Justice Claims (edited by Rickie Solinger, Madeline Fox, and Kayhan Irani), as well as Francesca Polletta’s It Was Like a Fever: Storytelling in Protest and Politics all do an excellent job of emphasizing the potential of stories to inspire meaningful action for change. Marshall Ganz echoes this in his heartfelt article “Why Stories Matter: The Art and Craft of Social Change.”

What is missing, however, is literature that addresses the very point at which foodlore and the act of storytelling with the intention of creating social change meet. I have trouble believing I am the first person to write about this intersection, but I have yet to find any books or articles that speak to this focus.

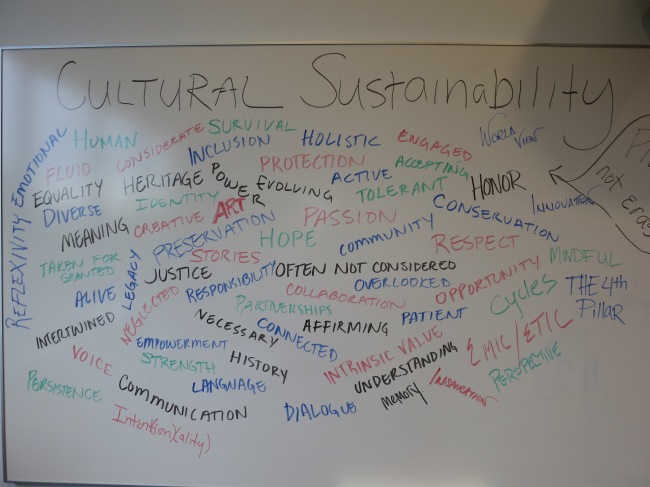

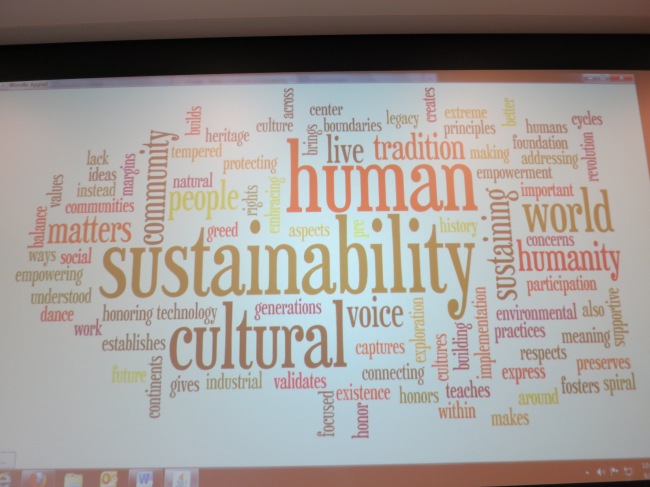

I am so grateful to have been able to attend the Cultural Sustainability Symposium this past weekend in Craftsbury, Vermont. The Symposium was a collaborative effort between the Goucher College MACS program, Sterling College, and the Vermont Folklife Center, and it brought together a brilliant crowd of folks (folklorists, ethnomusicologists, farmers, and more) who are all engaged in shaping this incredible field. One of the most inspiring presentations at the Symposium was given by Rosann Kent, the Director of the Appalachian Studies Center at the University in North Georgia. Rosann (who has an MA in Storytelling!) spoke about the SAGAS (Saving Appalachia’s Gardens and Stories) project at UNG, through which students combined oral history, seed banking, and quilting to save heirloom seeds, document stories, and strengthen the bonds of a place-based community. I was stunned by how transformative this project is, and it is the first example I have come across that exemplifies foodlore activism. SAGAS developed intergenerational and cross-cultural connections, emphasized the worth of traditional farming techniques and heirloom seed varieties, empowered longtime residents to tell their stories, established an organic garden and seed bank, and resulted in the creation of a beautiful community quilt as an art piece – all by working at the intersection of foodlore activism. I will be using the SAGAS project as a case study in my Groundwork Project.

Any suggestions on sources that directly address foodlore activism are appreciated!